Liu Xiadong‘s paintings are modern — meaning they are of this time — and they look Western to me. The thick application of the paint, the rough expressive brush work, it’s the legacy of painters like John Singer Sergeant or the California school painters, some of whom taught my teachers. Painters like David Park and Richard Diebenkorn. Liu Xiadong is Chinese — he studied painting in China — but there is nothing particularly Chinese to my eye about these paintings.

|

|

Left: Figures in a Landscape, David Park, via Flickr, Creative Commons. Right: Broken Rib, Liu Xiadong, via SAAM, courtesy of the artist

I ask about this — about whether the artist has deliberately rejected the traditional notions of Chinese painting or if it’s simply not that intentional. My interest isn’t so much geographic as historical — it’s about the technique. The curator, Josh Yiu, who leads the tour I’m on and acts as a translator for the artist, says that oil painting has been happening in China for about a hundred years now and that is how Liu Xiadong has been trained, as an oil painter.

I’m unsatisfied with this answer because China is not 100 years old. And oil painting is much older than that; oils become a standard material for European artists in the 15th century. As for Chinese painting, there are examples of representational painting from as early as 475 BC. That’s more than two millennium prior to the work of the artist currently on display at the Seattle Asian Art Museum. I want to push the point, but I opt for diplomacy. (The curator also states that the work is apolitical, something I have trouble swallowing given that the artist also has a body of work about the Three Gorges Dam project. Construction of the dam displaced hundreds of thousands of people.) Later, I notice the detail with which the artist himself studies a traditional hanging scroll, a faded image of a crane flying over some brushwork landscape and I wonder what he’s thinking.

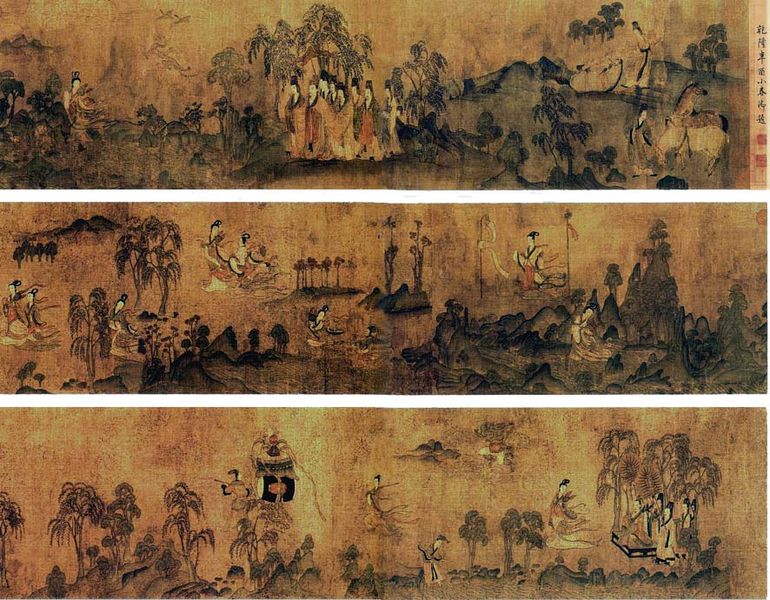

Nymph of the Luo River, 13th century Song Dynasty copy of original by Gu Kaizhi; ink and colors on silk via Wikimedia, Creative Commons

I look at art on several levels. First, there’s just the visual. I like the work displayed in Hometown Boy. I like the skilled painting, the bright color. These are paintings for artists that like paint. The subject matter is interesting too. There’s an unflinching look at the clutter and in some cases, despair, of exurban life. I like the weirdness of “Broken Rib.” There’s clearly a story here. Why are these shirtless guys looking at an X-ray on the edge of a cornfield? Where’s the clinic? Where are their shirts?

But I’m also interested in the historical and cultural context of what influences how art is made. Placing the David Park and the Liu Xiadong paintings side by side, I see such an obvious connection between the two.

Some time back, we started to see an influx of Vietnamese painting here in Seattle. There were attractive canvases on display with shiny red lacquer color backgrounds, abstract elements on the surface. Not long after that work appeared in galleries in Seattle, I went to Vietnam where this particular style of work was available everywhere. It was a commodity. Liu Xiadong’s work doesn’t feel like a commodity, it’s personalized by the very human portraiture. I studied, for some time, a picture of a man gazing into the middle distance, past his television. It’s a compelling piece and there’s something very sad about it, plus, it’s gorgeously painted. But I felt like the method was a commodity, if not the work itself. That’s a former painter talking, take it for what it’s worth.

This work defies the notion of what Chinese painting is. I remain curious about this concept, curious about what defines modern Chinese painting. Maybe globalization means that nothing defines it anymore. Or that everything does, from American painter David Park to Tang dynasty painter Gu Kaizhi.

Hometown Boy is at the Seattle Asian Art Museum until June 2014.

—

This post was sponsored by Grammarly, the online grammar check service. Good grammar matters, even when you’re writing about art.

From a (former) China historian’s perspective: While I agree that oil painting in China probably has a history of more than 100 yrs, I wouldn’t be surprised if it were not much more than 100. Western nations didn’t begin to carve out spheres of influence in China until the 1830s (see: Opium Wars). Of course there was contact with the west before then but the Ming and Qing were certain of Chinese supremacy in all aspects of art, literature, science, and intellectual life in general. Westerners really were considered barbarians, and they were admired for nothing. China was, to those in charge (and intellectual life in China under the dynasties was highly structured), truly the center of the earth, in all respects.

It was Japan that first looked to the West in terms of science etc., in the late 1800s, in a bid to modernize and strengthen itself against Western intrusions. Chinese students/intellectuals (who had been seeing their own country carved up by Westerners) in Japan (and, to a lesser extent, Russia) were exposed to all these “new” ways of thinking, of doing art, of approaching science, literature, etc. It appealed to them because it was they way of thinking/doing of countries stronger than their own. They brought it home and initiated a “self-strengthening movement.” From this grew the radicalism that led to the 1911 Republican Revolution and the overthrow of the Qing dynasty. (The cutting of quews, the banning of foot binding, the promotion of education for women, and other “modern” developments soon followed.)

A simplified version of events, obviously. Long story short exposure to the West didn’t lead to “westernization” of arts etc in China till the 1900s. Leading up to, and after, the Revolution western intellectualism was embraced with a fervor — by a certain (small) segment of the population.

RIGHT. What you said (I think). That’s why this interests me. It’s such a clear rejection of Chinese style. And what I wanted to know was — was this an active choice on the part of the artist, or an “accident” of his being educated in Western style painting? I’m not dismissing his skill, but in a the context of Chinese painting — and this stuff is on display at the Asian Art Museum, so it is totally contextualized — where’s the artist come down on his place in Chinese art history?

Sidebar: YAY for brainiac art discussion in the comments! YAY!